Why have millions of people left Italy to embark on a journey of hope towards America?

It was March 17, 1861 and Italy was experiencing an epochal change: the unity of the nation was proclaimed.

It was a period of great change and for many reasons, a great exodus began. Italy wasn’t a homogeneous country, it was still divided by society, culture and language.

Emigration did not only come from the south; on the contrary, towards the end of the nineteenth century, the north would also contribute to increasing this phenomenon.

Regions such as Liguria, Piedmont, Lombardy, Veneto, Tuscany, and even territories not yet Italian, such as Trentino and Friuli, fueled an impressive flow of individuals and families across borders, both to Europe and overseas.

In the collective imagination of Italians, Argentina, Brazil and the United States became the so called “Merica”. These countries represented the hope of a better life and unexplored opportunities.

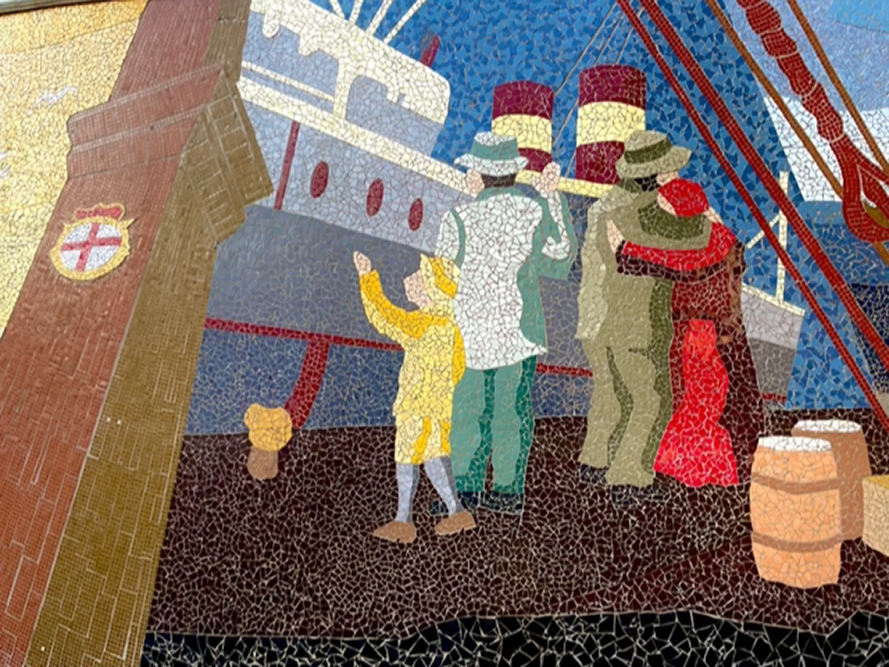

Over the years, emigration spread to virtually all regions, reaching its peak on the eve of World War I. This incredible flow of people was also facilitated by the change occurring in the means of transportation.

Steam navigation had been switched to and passenger steamers had become larger and larger. The main shipping companies began to sell tickets and the resonance of wealth that could be found in America now reached the most remote countryside.

Thousands of people impoverished by hunger, banditry, and disease decided to sell their land and homes to buy a one-way ticket to a hopeful but uncertain future.

The journey of emigrants with a third-class ticket

On board the ships, conditions were extremely difficult. The dormitories were cramped and humid spaces, designed to accommodate as many people as possible.

Emigrants were only allowed to bring a bundle, a sack or a box of clothing and groceries, while everything else went into the baggage compartment, which remained closed for the entire duration of the journey.

This forced the emigrants to stay in the same clothes the entire journey, often wet from the rain or soiled with food, urine or vomit.

Male and female dormitories

To avoid promiscuity, men and women were separated in dormitories.

Regardless of gender, the spaces were overcrowded and unsanitary, with dirty, smelly people sleeping together with no chance to wash.

The stench became unbearable at times, prompting many to prefer to be outdoors, albeit in the cold and in uncomfortable conditions.

This became impossible during winter crossings of the North Atlantic, due to frost and gales.

The women’s dormitories were described as vast, dimly lit mezzanines, with rows of bunks arranged one on top of the other.

The situation became complex with the presence of women, young and elderly people, children and pregnant women.

This environment became the place where the most serious diseases manifested themselves, affecting especially the youngest and causing epidemics with often disastrous outcomes.

Sanitary conditions and order on board

From 1895, for voyages beyond Suez and Gibraltar, the presence of the ship’s doctor became mandatory.

The lack of proper hygienic conditions and the crowds of people fostered infections, epidemics and diseases.

The ship’s doctor proved to be essential in dealing with the precarious conditions while using primitive tools and few medicines.

On board the ships, the Royal Commissioner of Emigration held a power comparable to that of the commander.

He was responsible for administration, mail management, overseeing order, and settling disputes between third-class passengers.

Anyone who gambled, kept weapons and alcoholic beverages on board, was an illegal immigrant or started a fight went straight to jail.

The commissioner also withheld passports and compiled the passenger list required by the United States for disembarkation.

Eating on board: food and refectory

Food on board was consumed in harsh conditions, with emigrants crouched and huddled below deck. Over the years, the quality of food changed depending on the company and travel, but it was still an improvement over the food difficulties that existed at home.

If it is true that many complained, for many emigrants it was perhaps the best aspect of the journey.

Many who fled to avoid starvation were faced with more than abundant rations including starchy food, but also vegetables, meat, salted fish, salad, tomato sauce and fruit.

And for many, it was a treat; the first real taste of that different life, also in terms of food abundance, to which they aspired with emigration.

To make the distribution of food easier, people were divided into groups of six called “ranci”.

Each group was assigned to a supervisor who had the task of collecting bowls with meals for the others. This system allowed everyone to receive their daily ration for both lunch and dinner.

Crouched on the deck by the stairs, with the plates between their legs and the bowl containing the meal between their feet, our emigrants ate like the poor at the doors of convents.

With these premises, imagine the hygienic conditions of the upper and lower deck of a steamship tossed by the sea.

For many years, emigrants’ food on board is consumed in this way: where they can find some place, on the deck if there is no bad weather, or in the dormitories if there is rain and gale.

Water was also a big problem. It was stored in large iron tanks lined with concrete. With the rolling of the ship, the latter tended to crumble, clouding the water that came into contact with the iron, oxidizing and being drunk unfiltered.

Once the meal was over, everyone had to wash their dishes, but without hot water and soap one can easily imagine the unpleasant result of that washing.

In the following years, larger ships introduced the first refectories, improving meal conditions during voyages to North America.

They were still very spartan, but they were a step up from the early days. Travelers had the opportunity to sit at a table, even if without tablecloths and napkins, and enjoy better meals.

After about 30/40 days of travel, the most resistant, lucky and healthy finally arrived in America.

At the sight of the Statue of Liberty, a cry of satisfaction rose in the air along with tears of emotion welling from their eyes.

The steamer stopped at Ellis Island and there, after disembarking, yet another story began.